Comorians who have been declared illegal by France on its occupied territory of Mayotte are under attack. The French authorities who currently occupy Mayotte, the main island of the Comoros, have declared war against “clandestine Comorian migrants”. An article from the French newspaper le Canard Enchainé has revealed the obscure machination of France’s Minister of Interior, Gérald Darmanain entitled “Wuambushu Operation” (23rd February 2023). It consists of a massive attack on Comorians deemed migrants since they have moved to Mayotte from the other islands of the Comoros archipelago without the legal visa imposed by the French authorities. The Wuambushu project targets Comorian migrants with the destruction of their informal and precarious habitats and seek their deportation from the island of Mayotte. The number of illegal Comorian immigrants in Mayotte is deemed to be between 50,000 and 55,000 people (https://www.senat.fr/rap/r07-461/r07-4615.html). The communiqué from the left polical party LFI/NUPES of France states that the operation is scheduled to take place between 22nd April to17th July 2023. The Reunion Island online media platform clicanoo.fr has revealed that this operation will mobilise around 1700 police agents with 500 agents coming from metropolitan France. The much controversial police unit called CRS 8 which is a rapid intervention unit specialised in urban violence will be deployed from France as well.

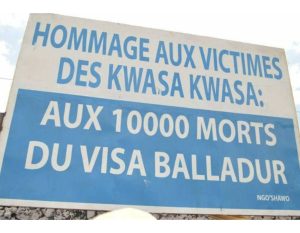

The deportation of Comorians from Mayotte is the direct consequence of the Balladur visa introduced in 1995 by the French government in Mayotte. It subjects the movement of the Comorian people to Mayotte to the obligation of obtaining a visa from the local French authorities before entry into Mayotte. Prior movements from across all Comoros islands to Mayotte could be considered were free and unrestrained. The 1995 French decision has not only contributed in creating more division between the people of the Comoros archipelago (Mayotte and the rest) but has favoured illegal movements from mainly Nzwani to Mayotte. These movements have in turn created a new morbid economy of precarious boats known as Kwasa Kwasa, transporting Comorians across a distance of 70 kms to Mayotte. Mohamed Said Moudjib, the President of the associative movement NGO’SHAWO from the Comoros affirms that the passage price on a Kwasa Kwasa from Nzwani to Mayotte has increased since the introduction of the Balladur visa. It is notoriously known as the death visa to locals. From costing around 100 Euros in 1995, the trip now can cost up to 500 Euros with nearly 50 persons piled up in a boat that should not contain more than 10. In an open letter published by the French media, the Fondation des Comores, in response to Emmanuel Macron’s cynical allusion to the Kwasa Kwasa, revealed the figures of 10,000 people who have died at sea in 12 years since the introduction of the Balladur Visa. Furthermore, according to the Fondation des Comores, the Balladur visa has, in effect, created a situation where most Comorians who have left their indigenous islands to go to Mayotte do not return home due to the difficulty to obtain the visa, thus leading to the current situation of “illegal migrants” (declared as such as by the colonial French power) entrapped in slums and survival conditions in Mayotte.

The primary aim of those risking their life in the hazardous boats to populate the slum of Kawéni next to Mamoudzou, the capital city of Mayotte, is to be found mainly in the disastrous socio-economic and political situation of the Comoros. The country is, indeed, ranked 28th poorest country in the world with 86.57% of its population living on less than 10 dollars per day. These figures have not been updated since 2013. However, given the global affliction of Covid-19 and the subsequent economic crises, the socio-economic conditions of Comorians have most probably worsened. According to an article from la Gazette des Comores , the inflation rate for the country in November 2022 was at 18.2%. Electricity alone cost 65% more in November 2022 as compared to November 2021. Life expectancy for Comorians was at 67.4 years in 2019, 10 years lesser than for residents of Mayotte. The political situation is no better. Since 1970’s, the country has experienced 9 attempted coups and severe periods of political tensions, the most important of which was the secessionist movement from Zwani in 1997. Not only did the movement fiercely advocated for separation from the Comoros Union, but it also demanded the integration of their island, Zwani, with France.

However, the political instability of the Comoros cannot be imputed to the sole power-driven trait of Comorian politics. Arguably, the autocratic and despotic rule of Comorian political leaders who adopted anti-democratic measures must be condemned, for example; the contemporary President of the Comores, Azali Assoumani, deliberately altered the constitution in 2018 so as to remain in power and exert more authority. However, the instability that seems to be an endemic feature of the Comoros Union is primarily due to France’s exertion of colonial dominance in the archipelago. Obscure figures have been involved in the shaping of French power in Mayotte. France was intensely involved in political interference and destabilisation in the Comoros over a period of 25 years since the 1970’s. French mercenary, Bob Dénard, was directly responsible for no less than 4 putsch in the archipelago resulting in decades of political unrest. Bob Dénard even worked with the former apartheid regime of South Africa in to orchestrate political violence in the Comoros illustrating how France had recourse to the worst possible forms of dangerous intervention in local politics across the Comorian archipelago. The primary cause of the archipelago’s instability is France’s violation of Comoros’ territorial and sovereign integrity when it was engaged in the process of struggling for its independence. Indeed, when France organised the independence referendum for the whole archipelago in December 1974, the plan was to consider the consolidated will of the whole archipelago for independence from France. 95% of Comorians voted as one territory in favour of independence, however, this demand for sovereignty for the whole archipelago did not suit France’s geostrategy in the Indian Ocean. A separate vote was orchestrated later that considered the view of voters per island. Mayotte voted against independence and it resulted in the dismembering of the Comoros archipelago.

The will for Mayotte to stay under French colonial rule can be understood from the fact that the French colonial administration and elites were historically concentrated in Mayotte and the latter did not want to lose any of their existing privileges under a new independent flag. However, the privileges of Mahorans (citizens of Mayotte) with regard to their Comorian brothers and sisters do not equate with metropolitan France’s living conditions. Indeed, if Mahorans enjoy a better standard of living than the rest of the archipelago, they are on the contrary, by far, the poorest French overseas department. One may argue that the migratory flux hailing from the other Comorian islands to Mayotte is putting a strain on the capacity of the French authorities to ensure better services to Mayotte’s citizens. However, figures on Mayotte’s public health services clearly demonstrate the socio-economic distress of the island that set off the red alarm of the authorities during the Covid-19 pandemic. Official figures from pre-pandemic period (January 2019) from the France public agency Agence Regionale de Santé give a clear picture of the lower socio-economic conditions in Mayotte as compared to other overseas French territories and the metropole. One example is the fact that, in 2019, there was only one generalist doctor for nearly 1850 individuals in Mayotte as compared to nearby Reunion Island (also a French dependency) where 719 inhabitants could access 1 generalist doctor.

Mahorans face a between the hammer and the anvil situation, stranded between poverty and the influx of Comorian migrants that is fuelling xenophobia and far right opinions among both politicians and citizens. On 27th of October 2003, Moussa Madi, the Mayor of Brandélé commune found in the south-east part of Mayotte illegally ordered the burning down of around 30 houses occupied by Comorians living in the Hamouro village. The Wuambushu Operation that France seeks to implement aims at bulldozing Comorians’ houses in Mayotte now is a similar destructive process. As such, France is deliberately replicating the act of violence perpetrated by the Mayor in 2003. The current Wuambushu operation legitimises the former illegal act of burning down the Comorian migrants’ home. By implementing the Wuambushu operation, France will exacerbate tensions between Mahorans and Comorians and, thus, perpetuate its colonial politics of divide and rule against a population that has been repeatedly politically divided to serve France’s interests in the region. These interests are neither the ones of the Comoros archipelago people, including Mayotte, nor the ones of the Indian Ocean people. Moreover, France’s stranglehold on Mayotte is in total violation of regional resolutions (African Union, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Islamic Conference and the League of Arab States) and international resolutions such as the UN Resolutions 3385 that reaffirm the territorial integrity of the Comoro Archipelago including Mayotte. The only reason why France is persisting in maintaining Mayotte as its territory, in disregard of regional or international opinions and institutions, is for strategic and military purposes. Firstly, France seeks geopolitical control over Mayotte’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends to 74,000 KM2. This extensive marine zone contributes in making France the world’s second largest EEZ in the world with important access to halieutic and marine resources. Secondly, and, most importantly, French military presence in the region is crucial for ensuring the country’s neoliberal policies of control over fossil fuel and other resources in the Indian Ocean and the Southeastern region of Africa.

Since 2007, intense marine research is being conducted in the south-west Indian Ocean region and it has led to the discovery of important natural gas deposits in the region. Mayotte’s geographical position gives France the upper hand in the advent of exploitation of this reserve in the South West Indian Ocean. Along with access to exploitation, Mayotte will give France the security requirements that come with fossil fuels exploitation. The FAZSOI (Forces armées de la zone sud de l’océan Indien) is the French army in the Indian Ocean that has resources in Reunion and Mayotte. It is now busy engaging in regional partnership with armies from neighbouring countries such as Tanzania, South Africa and Madagascar, etc. The imperative to foster French militarisation in the Indian Ocean is based on the threat represented by China’s imperial advance in the region (China is operating a military base in Djibouti). The FAZSOI is actively involved in the training of local forces in Mozambique in the region of Gabo Delgado in the northern part of Mozambique where there have been major security issues. The Gabo Delgado province is the reserve of important liquid natural gas where the French transnational company, Total, has already implemented itself as prime exploiter. Total which is also active in the destruction of important biodiversity reserves in Uganda and Tanzania with the EACOP pipeline project is actively benefiting from the security that French military forces are likely to provide in the region to French multinational companies and their interests particularly since they will be using the Dar Es Salaam port for their polluting business link with the EACOP pipeline.

The Wuambushu project and the expansion of French military occupation of Mayotte pose serious threats to people from the Indian Ocean region, from a security point of view in the advent of any dispute or conflict in the region for control over fossil fuel reserves and from an ecological perspective. In the recent years, social movements from South West Indian Ocean region have been claiming the revival of the 2832 United Nations Resolution for the declaration of the Indian Ocean as a peace zone. This 1971 initiative has been sabotaged by imperialist states namely UK, France and US. In the contemporary global climate tension that is pushing the world towards an impending cold war, voices of people demanding regional peace in the Indian Ocean are critical. Not only do they demand that their respective countries do not become belligerent in any conflict that will put their people at risk, but they are also claiming back their sovereignty over economic and political decisions. Their territorial sovereignty and decision-making capacity in the region have been undermined in colonial and post-colonial power relationships with current imperialist and sub-imperialists powers in the region namely France, India, China, UK, South Africa and the USA. Peace is not only about not wanting war; it is about the manner in which nations relate to another and the impact it has on ordinary lives of citizens. It involves sovereignty and self-determination for nations entrapped in global geopolitics of warring imperial nations. Indian Ocean people demand their voices to be heard. Should relations between nations be based on mutual cooperation and aid? Or, should they be determined by domination and threat? And these questions may also be raised when addressing a people’s relation with ecosystems? Should local territories be used in the promotion of war and destruction without local consent or should people’s livelihood be prioritised through their self-determination and control over their sovereign territories?

Let us be clear: maintaining imperialist forces in the Indian Ocean region will never allow local people to achieve sovereignty in the region. Fossil fuel exploration or exploitation, for example, are not high on the agenda of insular states from Indian Ocean region. They do not have the technological means of exploration. In the quest of fossil fuel exploitation, these states only become facilitators for petroleum corporations. They derive insignificant financial gain from such investments by the predatory fossil fuels industry. In contrast, the people, their immediate ecosystems and future generations become bearers of all the pollution and contamination that fossil fuel industrialisation brings. From a deeper perspective, insular states from the Indian-Ocean and elsewhere should in no way be accomplices of the fossil fuel agenda. The contribution of fossil fuel industry in the accumulation of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere is only disputed today by far right extremist political figures with no scientific-based evidence. In its sixth assessment report of 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had already warned that intensity of cyclones in the Indian Ocean region would dramatically rise due to the fact that it is the ocean that is most subject to global warming. In February and March 2023, cyclone Freddy crossed the whole Indian Ocean laterally and its destructive path testifies as to the correct prediction of the IPCC. As an unprecedented climate crisis phenomenon, it was a record breaker on several aspects. Never has a cyclone lived for so long; travelled such a long distance going back and forth the Mozambican channel and striking land with such intensity. Based on IPCC observations, cyclones with Freddy’s destructive intensity will be norm in the coming years.

The Wuambushu Operation is not only about the deportation of thousands of alleged clandestine Comorians by the French authority. This operation’s implications are anchored in the imperial history and ongoing colonisation of Indian Ocean islands. This project should be severely condemned by institutions like the United Nations, the African Union, the South African Development Community, the Indian Ocean Commission and, of course, by all regional governments and the people from the region. This scandalous operation is being conducted on an occupied territory and it is a serious violation to the human rights of the Indian Ocean people, their desire to live in peace and their capacity to define serenely together ways and means of collaboration to ensure livelihoods, resilience and ways of adapting to the climate-induced catastrophe era that the people are already facing.